|

Filliol Family History

The Filliol clan descended from the French Huguenots.

About twenty years ago my mother, Aline (Murphy) Filliol, gave me a lovely gold Huguenot Cross pin. I had it made into a necklace because I was afraid if I wore the pin I would lose it.

I cherish it and wear it proudly as an ancestor of the French Huguenots. It is a reminder of those brave people who suffered for their faith in France.

The Huguenot cross is the distinctive emblem of the Huguenots (croix huguenote). It is now an official symbol of the Eglise des Protestants reformé (French Protestant church). Huguenot descendants sometimes display this symbol as a sign of reconnaissance (recognition) between them.

My Huguenot Cross

|

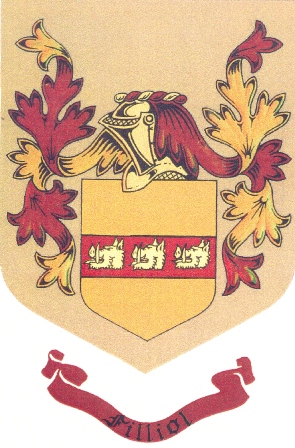

The Filliol family crest

|

My Paternal Grandparents

This is my Grandfather, Philippe Filliol with his first wife, Julia (Jospin).

Photo taken 1922. Notice the phone on the table!

|

My Grandmother, Julia, was born in 1890. She and my grandfather were twenty-four years old when they got married.

My grandparents were the directors of "Le Foyer des Jeunes". This was a ministry owned by a protestant board to house young men cheaply who were either students or visiting Paris or working for a time. There were about sixty rooms in the building. A part of this was a restaurant which served some four hundred men who worked in the factories near by. The meals were cheap. About fifteen waitresses looked after the work in the restaurant. My grandfather went to Les Halles every morning to get the provisions and then went in the kitchen to help with the meals. The service had to be quick and efficient. The restaurant was open at night but only for the residents. My grandfather went down every night to discuss politics with all the young men.

Le Foyer des Jeunes does not exist anymore. It was situated at 151 Avenue Ledru Rollin in the 11th Arrondissement; very close to La Bastille.

This was the restaurant at Le Foyer des Jeunes.

|

My sister, Lucy, went to France in 2003

and took this picture of the building where my Dad was born.

My grandparents lived on the top floor.

|

I never met my father's blood mother,

Julia (Jospin) Filliol.

|

Julia (Jospin) Filliol on the farm,

Cornwall, Ontario, Canada.

|

My Grandfather Filliol on the farm,

Cornwall, Ontario, Canada.

|

Philippe and Lucie (Trocqueme) Filliol, Haiti, 1958

This is my grandfather's second wife.

|

This is how I remember my grandmother,

Lucie (Torcqueme) Filliol, 1976.

|

My grandfather, Philippe Filliol remarried after Julia died, to Lucie (Torcqueme) when my father was twenty-eight years old. Lucie was a cousin to my father's blood mother, whom he knew from Young People's groups they attended together in France.

My grandfather, Philippe Filliol, died when I was eleven years old. I don't remember him much, but I do remember my grandfather as a gracious, kind, and quiet man. When he came to Canada my grandfather became a pastor.

When my grandfather died I remember my father sobbing his heart out in the bathroom of our house. I will never forget that.

I have fond memories of my grandmother, Lucie Filliol. She was very prime and proper. I remember that she set her table with more than one fork and spoon and I never knew which ones to use for what. I do remember her kindly showing me which spoon to use for soup. Her tables have lovely white linen tablecloths and napkins. Even though she never had any children of her own (she was too old for children once she married my grandfather) she was sweet and patient with me and my four other siblings.

I remember the Christmas holidays when she would come and visit and she would have a small holiday envelope with money in it for each of us children. She also always brought a "Buche" (yule log) each New Year's Day. I remember the little ax on it and the tin foil little sign on it that said "Joyeux Noel". I cherish my French heritage, especially the outstanding Christian example that my grandparents were to me during my formative years.

Grandma Filliol

always brought a "Buche" for New Years.

|

It was difficult for us children to communicate with my grandmother because of the language barrier. She spoke French with very little knowledge of English. My Dad and Mom spoke french and english in our home. We children went to english schools because at the time in Canada, English schools were protestant and french schools were Catholic. We were protestant so we went to english schools. Even though my parents communicated some in French in the home, I was never very fluent. I could understand the drift of most conversations, but talking back in French was another matter.

Here I am reading the Bible to my Grandmother Filliol in 1976.

|

I feel sad that I wasn't able to communicate more with my grandmother. I would have loved to have known her better and have understood about her life in France. I think she had a lonely life because of the language barrier.

After my first child, Jennifer, was born, we took a trip back home from Guelph to Cornwal and went to visit my grandmother who was in a nursing home at the time. Despite the communication barrier, love was shared between us. I cherish those memories.

Here I am at age twenty-two, with my paternal grandmother.

She is holding my first born, Jennifer, at six months of age.

|

My father had two brothers and one sister. The oldest, Yves Filliol, was born in November 1914. He was killed on the Belgium border in May 1940 just before France felled to the Germans. It is hard to imagine a twenty-six year old---so young and so courageous. My grandmother, Julia, was dying of cancer at the time of his death and no one had the heart to tell her that Yves had died in the war. I never met Yves, of course. Next is Michel who was born in 1918. I vaguly remember him, whom we all called "Uncle Michou." He lived in France much of his life and died about two years ago in Aix-en-Provence. He has one daughter, Catherine. My Dad is next. He was born in 1922.

My Dad's siblings: Monique, my Dad, Michel and Yves.

|

The last child and only daughter, is Monique who was born in 1926. She was twelve years old when they came to Canada. She left Cornwall in Septebmer 1946 to go to nurses training in Montreal. She graduated in August 1949 and then married the love of her life, Robert, on August 10th. (Also Gerald's and my wedding anniversary!)

I remember her the most, Monique (Filliol) MacBeth. She was "Aunt Monique" to me and she always impressed me with her stylish clothes and her great beauty. She was very sweet, kind, generous and affectionate. If is funny that as a child you don't really connect "this is my Dad's sister", only that she was my aunt somehow or other. Aunt Monique lived "out west" (Canada) and was married to a doctor, Robert MacBeth or "Uncle Bob" to me. They had four daughters. Even though we didn't see my cousins often, when we did it was a great time! My Aunt Monique currently lives in Toronto. I have not seen my Aunt Monique since my childhood.

Aunt Monique has recently been in touch with me and updated me a bit on my cousins and what they are all doing. She also corrected some of the above family history. Thank you, Aunt Monique!

My Aunt Monique and Uncle Bob and their d aughters. August 2013.

From left to right: Nicole, Danielle, Joanne and Michele.

noticed Michele is wearing the Huguenot cross.

|

My cousins (Aunt Monique's daughters) are Michele, Nicole, Danielle and Joanne.

Michelle and her husband Harold have four children. The eldest, Joanna, lives in England in a village and her husband is a farmer. They have Violet, Freddie, and a new baby born in June 2013. Lindsay is next. She and her husband, Devin, who is a policeman, live in Calgary. They have two boys; Carter and Travis. Adrienne and her husband Andrew also live in Calgary. Rob is the last, married to Amy and they have a boy, Callum.

Michele ran a nursery school for twenty-five years and has now retired.

Michele and Harold at my Dad's funeral, May, 2013.

|

Nicole is next. She is married to David who is a manager at Ontario Hydro. They have two children, Duncan and Meredith. Nicole has worked for the last thirty years or so at a children's hospital.

Danielle is married to John. They both have Ph.D's in Philosophy living in a college town near Philadelphia. Danielle is a professor at Haverford College. They have one son, Alexander.

Joanne is married to Paul. Joanne works as a manager in public health. She and Paul, who is a vice president in a big construction company, have two children; Julia, and Daniel.

Aunt Monique has been married to Uncle Bob for sixty-three years, as of 2013.

My Maternal Grandparents

Alexander Murphy and Heloise (Lavictoire)

on their wedding day October 30, 1899

|

My mom with her siblings and her parents.

She is the little girl in the front/middle.

|

First row left to right: Louise, My grandmother Heloise, my mom Aline (Murphy) Filliol, my grandmother Alexander, and John.

Second row: Ida, Joseph, Pat, Tom, twins Dolores & Dollard, and Yvonne.

Third row: Leo, Dominic, Dave, and Sam.

My mom had a sister named Agnes who died of diphtheria when she was three years old.

My mother's maiden name is Murphy. The Murphy ancestors were soldiers under King James. They were from Cork County, Ireland.

Her ancestors, between 1832 and 1848, immigrated from Ireland to Canada. They left Ireland because of the potato famine.

These were the good times....and then the famine hit.

|

They came to a camp in Grosses Ile, Quebec where Irish Potato famine immigrants were based before being received as Canadian citizens.

My Mom visited there several years ago and said it was a very sad place. There were whole families who left Ireland, some died during the voyage, some contracted T.B. and died a short time after arriving in Canada. Some were teenagers who were sent by their parents to come to work in Canada. These teenagers were placed with farmers and even adopted by these families and that is the reason some of the Irish immigrants speak French. My mom enjoyed her visit to Grosses Iles but her heart was really sad and at one point tears just came pouring out. She was so troubled by the plight of these poor people.

Grosses Ile, Quebec, Canada.

|

....the largest immigration of the Irish to Canada occurred during the mid nineteenth century. The Great Irish Potato Famine of 1847 was the cause of death, mainly from starvation, of over a million Irish. It was also the motivation behind the mass exodus of hundreds of thousands of Irish to North America. Because passage to Canada was less expensive than passage to the United States, Canada was the recipient of some of the most destitute and bereft Irish.

Passage was difficult for those making the three thousand mile voyage from Ireland. Crammed into steerage for over six weeks, these "Coffin Ships" were a breeding ground for many diseases. The primary destination for most of these ships was the port of Québec and the mandatory stop at the quarantine island of Grosse Ile. By June of 1847, the port of Québec became so overwhelmed, that dozens of ships carrying over 14,000 Irish queued for days to make landing. It is estimated that almost 5,000 Irish died on Grosse Ile and it is known to be the largest Irish burial ground exclusive of Ireland.

Memorial cross for all the Irish immigrants that died on Grosse Ile.

|

Irish Immigrants on Grosse Ile

Between 1832 and 1848, emigrants poured out of Ireland. A deadly combination of an agricultural pathogen, and draconian colonial policy left millions starving. Great Britain operated Ireland under a “cottage” or “cottier” system. Irish tenants rented a plot of land in exchange for agricultural labor. The most fecund plots were reserved for British grain production. The Irish were often left with land that lacked adequate topsoil and key nutrients and supported only the monoculture of potatoes. When Phytopthora infestans caused the repeated failure of the potato crop, millions of Irish were left with no food or resources. British land holdings continued to produce grains for export during the famine, but the Irish were not allowed access to this food.

There is disagreement about whether these colonial policies were deliberately oppressive, or simply in stride with prevailing laissez-faire economic mores. The British government is purported to have viewed the famine as an opportunity to implement long-desired changes within Ireland – it was not a secret that they wished the Irish would leave Great Britain. The British in part subsidized the Irish exodus from Ireland by offering places on timber ships for the destitute – but these ships were meant for lumber, not people. These ill-equipped and dank ships were often turned away from major North American cities and diverted to Canada. As a British colony, Canada could not refuse British ships. The immigrants underwent a mandatory medical inspection when entering the country. Those who did not pass the inspection were held at Grosse Ile.

Starved people in close quarters for a long boat ride over rough seas is a pathogen’s wildest fantasy. Many arrived suffering from cholera, dysentery, and typhus. However, Grosse Ile did not provide respite from the suffering. Patients were ushered off of boats and into a crisis situation. The Medical Commission of Canada reported miserable conditions on Grosse Ile in the summer of 1847: corpses remained in beds with living patients and vermin ate the dead laying on the beach. Inexperienced staff, improvised facilities, and ignorance of disease prevented effective management of quarantined individuals.

Neither the British nor Canadian government took action to improve conditions on Grosse Ile. Canadian nationalists at the time believed that the Irish immigrants had habits that caused a predisposition to infection and sickness, and the well-documented anti-Irish sentiments in the United States were mirrored in Canada. Policies were in place that allowed disease and starvation to “naturally” decimate a disenfranchised population. Epidemics should be managed using empirically gathered evidence, not by prejudice against a group of people.

A large commemorative Celtic cross and a memorial listing the names of the dead stand on Grosse Ile. However, it’s easy to forget that Grosse Ile is the site of a mass grave when you’re participating in the nature walks and historical reenactments advertised on the Parks Canada website. Descriptions of the island’s tourism activities do not seem to reflect the somber atmosphere apropos of an island with such a morbid past. A mock medical exam and a tour of the mercury disinfection showers do not communicate the dismal conditions faced by quarantined immigrants.

Irish History on Grosse Ile

More on my Dad,Bernard Filliol

|

|